Story and Photos by Susan McKee

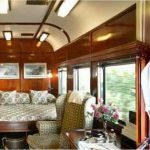

For those intrigued by the mysteries of gardens, the classical gardens of Suzhou in China are not to be missed. They are found some 850 miles from Beijing but only five hours away these days in the comfort of the bullet train.

For those intrigued by the mysteries of gardens, the classical gardens of Suzhou in China are not to be missed. They are found some 850 miles from Beijing but only five hours away these days in the comfort of the bullet train.

Classical gardens in China are a different species than those typical of North America and Europe. Instead of symmetrical plots of flowers bordered with clipped hedges, they resemble idealized landscapes, albeit in scaled down, compressed form. Those who constructed these gardens — often scholars and/or high government officials — were trying to bring natural scenery literally into their city backyards, combining architecture, rocks, water and seasonal plantings to mimic mountains, rivers and wilderness. The idea was to create the illusion of wandering through the natural landscape far beyond the garden, and the city, walls.

This style of garden was popular for more than a millennium, from the Northern Song to the late Qing dynasties (approximately from the 11th through the 19th centuries). Because of its temperate climate, more than 200 Classical Chinese Gardens existed at one time in Suzhou, a city in eastern China’s Jiangsu province. Now home to more than 10 million residents, it was founded in 514 BCE. Not far from Shanghai, it’s in the center of the Yangtze River Delta region.

Eight of that city’s 69 remaining gardens have been selected to represent the style as UNESCO World Heritage Sites. On a trip to China in November, I visited one of them, known as the Master of the Nets Garden. (You will find it in the Canglang District, Dai Cheng Qiao Road, No. 11 Kuo Jia Tou Xiang in Suzhou.)

The first garden on the site was constructed in 1140 by a government official of the Southern Song Dynasty who called it Ten Thousand Volume Hall (referring to the philosophical writings he’d collected that talked about the simple lives of Chinese fishermen). The garden passed through many hands through the centuries, but the emphasis on contemplating the fishing lifestyle was retained. It was renamed Master of the Nets Garden by its owner in 1785.

Classical Chinese gardens incorporate four elements: architecture (such as pavilions and study halls), seasonal planting (when I was there, fall’s flower — the chrysanthemum — was featured), rocks (especially pierced limestone quarried in the nearby Tai Lake) and water (which allows energy to flow easily).

All four elements are included in the Master of the Nets Garden, which is the smallest of those remaining in Suzhou.

It’s just about 1-1/3 acres and divided into east and west sections. Residential quarters are in the east: a linear arrangement of four halls, one tower and three courtyards. To the west, there’s an ensemble of structures around the Rosy Cloud Pool (a mere 3600 square feet). The water feature seems larger than it actually is because the small buildings are set out over the water and landscaping provides depth. Areas south of the pool were used for social activities, and those to the north reserved for intellectual pursuits.

The rock in the garden has a sculptural quality. Called Tai Hu, they’re limestone mined from Lake Tai, a freshwater lake near Suzhou. They include holes that allow qi (the life force) to flow freely, are slender with a rough texture, and are erected “top-heavy”. They represent wisdom and immortality.

All around the garden are “leak” windows — open lattice-work stone windows (each with a unique design) that allow the visitor to see the view “leaking” through.

Of course, there’s more than just this garden to visit in Suzhou. The other gardens on the UNESCO list of World Heritage Sites here are the Humble Administrator’s Garden, which (despite its name) is the largest Classical Chinese Garden in Suzhou.

Islands are a feature of both the Lingering Garden and the Retreat and Reflection Garden. The Lion Grove Garden is notable for its maze of pathways and rocks said to resemble lions.

The Surging Wave Pavilion is the oldest garden in the city’s UNESCO collection. Mountain Villa of Embracing Beauty emphasizes rock formations. Wall flowers are a key feature of the Garden of Cultivation. The Couple’s Garden is said to be especially romantic.

Noted Chinese-American architect I.M. Pei has said that he continues to draw inspiration from the Classical Chinese Gardens he visited in Suzhou at an early age (Pei was born there in 1917). He came out of retirement to design a new building for the Suzhou Museum, which opened in 2006.

Of course there’s more to Suzhou than its famous gardens. This city has been an epicenter of sericulture for centuries. Archaeological records point to silk cultivation in China as early as the Yangshao period (5000 – 10,000 BCE), but it was well established at least five millennia ago. Marco Polo, traveling along the trade route known as the Silk Road, visited Suzhou in 1276, and the country’s first silk museum was established here.

Visits to the city usually include a stop at the felicitously named Suzhou No. 1 Silk Factory. Of course, the primary purpose is to sell silk to tourists, but a visit includes a good introduction to the manufacture of this natural fiber from the raising of the silkworms on mulberry leaves through the deconstruction of the cocoons, spinning of the fiber and weaving of the fabric.

Just outside Suzhou is Tongli, a town called the “Venice of China” for its network of canals and pole boats reminiscent of gondolas. Water transport was once the norm (in fact, a 1,104-mile-long Grand Canal connected the Yangtze River Delta with the capital, Beijing).

You don’t need to travel to China to see a Suzhou-style garden, however. Portland, Oregon, and Suzhou are Sister Cities. One major result of this partnership (now more than two decades old) was the construction of a Classical Chinese Garden on America’s west coast.

The idea of Lan Su Garden began in 1985 when a group of Portland officials traveled to China to establish the Sister City relationship with Suzhou. Three years later, the Classical Chinese Garden Society was formed to begin garden planning.

Much of the work was carried out by artisans from Suzhou. Craftsmen constructed the wooden buildings and cast the 51 decorative “leak” windows. These were shipped to Oregon along with 500 tons of rock from Tai Lake. To complete the garden, some 65 Chinese workers (plus two cooks) came to Portland to construct the buildings and pathways. It opened to the public in 2000.

(Full disclosure: Susan McKee visited Suzhou as part of a “China Delights” tour sponsored by China Spree.)

Get Social