By Susan McKee

(Story and Photos)

Cuba: it’s complicated. Not only is there the privation caused by a half-century of economic embargo imposed by the United States, there’s the fact that at least one million Cubans have fled to welcoming shores.

What’s left behind is a society both proud and afraid: Cubans are gratified that they’ve been able to maintain their unique culture in the face of decades of adversity and fearful that what little they have achieved – free education and medical care are mentioned most often — will disappear with the embargo.

Crumbling Colonial architecture. Endless vistas of Caribbean blue seas. Music that still stirs the soul. And an artist whose work marks him as the love child of Barcelona’s Antonio Gaudi and Simon Rodia of Watts Towers fame.

The artist – José Rodríguez Fuster – is a painter, ceramist, graphic designer and more. Most famously, he uses broken crockery, paint, tile and such to embellish not only his home in the fishing town of Jaimanitas on the outskirts of Havana, but the homes of more than 80 of his neighbors.

The Colonial architecture of Old Havana gives a fin de siècle aura – that’s 1899, not 1999 — to that historic section of town along the waterfront. And the sea? It’s not far away anywhere on this narrow island nation.

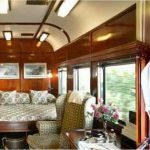

This writer was on a “people-to-people exchange” earlier this year – one of the dozen permissible reasons to visit. We were shepherded by a government-provided local guide, who joined us when we landed at the airport and never left us when we ventured out of the hotel, part of the Meliá chain based in Spain. Our transport on the island? A Chinese-made bus.

It’s not easy for an American to get to this Caribbean nation, even with the somewhat loosened restrictions. One must go with a licensed tour company and adhere to a preset agenda. At present, charter flights are the only option, although cruises are on the horizon. I paid about $2000 for five days/four nights in Havana with SmartTours and completed voluminous paperwork for the visa and other permissions.

On my trip, visits were arranged each day with local cultural and social service organizations – and each received a monetary “gift” from the tour operator. (Yes, Cuba finances these groups at least in part with fees charged to visitors.)

The visit to Casa Fuster – home of the artist – was one of the scheduled stops. We also listened to a choral group sing both Cuban and American standards, watched children risk their lives performing circus stunts, checked out a combination hair salon and barbershop museum, visited the University of Havana and toured Ernest Hemingway’s house.

The children – preteen boys and girls – learn circus skills after school in a converted movie theater. It was both breathtaking and terrifying to watch them risk serious injury completing seemingly impossible moves – a young boy soaring thirty feet above the concrete floor with nothing but aerial silks to suspend him, another balancing on an increasingly tall series of boards and balls, others in contortion acrobatics that were worthy of Cirque du Soleil.

The barbershop museum tucked away in a pedestrian alley is not only a collection of hair styling art and materiel, but a training school for aspiring stylists and a working salon. Its owner is using the proceeds to renovate the surrounding Santo Angelo neighborhood — his little corner of Old Havana.

Hemingway’s house, on a secluded 10-acre site east of Havana, is left much as it looked when he lived and wrotethere in the 1930s Visitors peer in the open windows of Finca Vigia (“lookout house”) to see his bedroom, office, dining room and a somewhat spooky collection of taxidermied animal heads (he was a big game hunter as well as a fisherman).

When we were visiting the University of Havana, a photographer in our group wanted to ascend the stairs to the mezzanine, so she could shoot a photo down toward where we sat in the two-story reception room adorned with enormous oil paintings depicting classical symbols of the Liberal Arts. Uh, no. She had to stay seated with the group.

At Muraleando, a local community center, we saw some of the artwork produced there, which has spilled out of the building (a repurposed water tank) to adorn the neighborhood.

A visit with Lorenzo Lopez, an artist recently returned to Cuba from Spain, provided a look at some of his work and a discussion of his vision for the future (which seemed to involve repurposing hundreds of reclaimed industrial parts).

There are no privately-owned restaurant businesses in Havana – instead, individuals are licensed by the state to operate paladars: small restaurants in what were private houses or apartments renovated for meal service. Finding a variety of foodstuffs is difficult in a country with crumbling infrastructure and virtually no imports (the U.S. embargo forbids companies doing business with the U.S. from doing business with Cuba), but paladar owners expand their offerings by growing vegetables, fruits and herbs.

The majority of Canadians, Europeans and South Americans who come to Cuba without the governmental restrictions hampering Americans head to the resort enclaves along Cuba’s beaches. My destination was Havana.

Having been to several Eastern Bloc nations not long after the demise of the Soviet Union, I was prepared to see a country stuck in a time warp. I wasn’t prepared for the pervasive decay: collapsing walls, damaged roofs, missing windows, rotting door frames, creeping mold and mildew. There wasn’t a window box or flower pot on a balcony anywhere.

The souvenirs for sale are virtually all handmade: oil paintings of Colonial buildings, fabric dolls, crocheted dresses, toy cars made from aluminum cans. Yes, Americans can now bring Cuban cigars back to the U.S., but the total spent on cigars and Cuban rum can total just $100 (and the best stogies are $25 each).

Torrential rains fell one afternoon. Streets turned into raging torrents. Even the windows in the hotel leaked, necessitating staunching the flow with bath towels. After our tour group got back to Miami, we read news reports that three Cubans died in Havana that day when more than three dozen buildings collapsed in the deluge.

According to our guide, approximately 20 percent of the Cuban population works in tourism (the largest industry), and earns “Middle Class” salaries in Cuban pesos that are convertible to foreign currencies (called “CUC” and pronounced “kooks”). The remainder are paid in non-convertible currency (“CUP”) and subsist at poverty level. Although they’re provided housing, they have no money – or available materials – to make repairs.

Those famous 1950s American cars? They’re tourist taxis, ferrying the nostalgic around town with completely refurbished exteriors and long-ago-replaced engines. It turns out that the majority of the vehicles in town are not classic Chevy BelAirs and Ford Fairlanes. They’re nondescript Kias, Hyundais, BMWs and Peugeots. There are no car dealerships in Cuba: each is imported individually from abroad and almost all (according to reports) are owned by the government or the 7% of the population with membership in the Communist party. Traffic jams are nonexistent: most Cubans ride bicycles or (if they’re lucky) Vespas or Kawasakis.

Get Social